The world can't afford another carbon cop out

Climate risk is unlike other macroeconomic risk. It demands urgent action from financial investors, global leaders, and civil society

Light-touch regulation was one of the main causes of the global financial crisis. Yet, policymakers could be sleepwalking into a new catastrophe if COP 21 fails to agree a global mandatory target to reduce carbon emissions.

It is not just coral reefs and polar bears that are under threat if temperatures continue to rise unchecked. Climate change is a long-term and potentially irreversible trend, which could result in huge losses for the global economy, the investment industry, and the savers, pensioners and beneficiaries that depend upon it for their own future too.

A rise of roughly 4°C in temperature could wipe an estimated $13.9 trillion off global asset values through to the end of the century, according to research by the Economist Intelligence Unit. That is close to the GDP of the world's third largest economy, Japan. If average temperatures rise by 6°C by 2100, we stand to lose up to $43 trillion. When considering that the combined capitalisation of global stock markets is currently around $70 trillion, the potential losses to governments, private companies and individuals could be enormous. If that is not enough to focus the minds of policymakers attending the Paris summit, nothing will.

At first glance, 2100 may seem way off. But managing the risks from climate change is unlike managing traditional financial market risks, such as sudden interest rate hikes or hyperinflation. We won't be able to apply a Band-Aid to make portfolios more resilient. Short-term fixes, behaviour that is sadly all too common in the financial markets, miss the point altogether. In essence, climate change is a macro-economic risk that will undermine all future assets through weaker growth and lower returns, cumulatively and over time. The longer it is left unaddressed, the bleaker the long-term outcome.

“ It is already too late to take remedial steps on the climate change the world will experience 35 years from now.”

At COP 21 we need policymakers to commit to firm targets for carbon emissions. At the time of writing, the cumulative impact of global commitments to reduce emissions would lead to 2.7°C of global warming if fully implemented; uncomfortably close to the 4°C rise that would cause almost $14 trillion of losses and not so far off the 6°C rise that would cause a financial catastrophe. The outcome from the Paris Summit must be a collective commitment to reduce emissions to a level where warming is limited to 2°C.

The financial industry has a key role to play in meeting that target. The first step in preventative action is to plug the disclosure gap to produce emissions data that is as timely, comparable and reliable as earnings data. The current lack of such disclosure by the majority of large listed companies prevents investors from factoring carbon and climate risk into portfolios. Governments, national regulators, stock exchanges and non-profit organisations have developed a plethora of schemes to address environmental disclosure over the last decade, but they tend to be voluntary, and hence have limited scope.

The International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO), the global hub for all securities regulators, must step in and enforce consistent reporting standards. Sceptics will recall how the 2009 Copenhagen Summit failed to reach an accord. However, with so much preparation and stage management ahead of COP 21, there is every reason to hope governments will arrive at a positive outcome this time around. In that event, IOSCO's role becomes crucial, so that good intentions translate into concrete action.

There is proof that a robust approach to transparency is effective. Each of the top-10 stock exchanges ranked in Corporate Knight Capital's Measuring Sustainability report are located in jurisdictions with broad and mandatory reporting requirements.

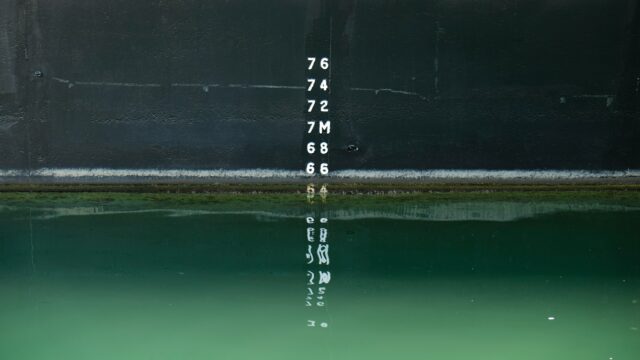

As civil society is well aware, effective disclosure is just the tip of the iceberg. Companies and investors subsequently need to be able to compare performance with others in their sector. Given that information, investors could more easily move money away from companies that score poorly on emissions and other sustainability measures; incentive enough for those companies to make the necessary improvements.

Beyond disclosure, governments can do more to correct the market failures; namely by establishing a material carbon price, either through fiscal measures, emissions trading schemes or by setting producer responsibility standards. This would put climate change at the centre of corporate valuations, and ensure capital is put to work in the right places.

For that to happen, COP 21 must lay firm foundations. Non-state actors, including investors and civil society, can then lead on the establishment of transparent benchmarks ranking corporate performance against climate change and other sustainability goals.

The world cannot afford a climate crisis. Global leaders must hammer out a pact with punch and IOSCO must deliver effective implementation. A fluffy cop out due to conflicting vested interests, haggling and excessive compromise would not be fit for purpose.

Euan Munro, Chief Executive Officer, Aviva Investors

This article originally appeared in Outreach - COP 21 - Edition 5 - Business, Investment and Innovation (December 2015, pg 1) published by Stakeholder Forum for a Sustainable Future.

Image credit: "greenhouse gas" (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) by Sky Noir