Seagrass meadows: battling the plastic tide

Richard Lilley is a marine ecologist and director of the marine conservation charity Project Seagrass. Here he gives his personal perspective on the conservation challenges facing the vital yet oft-overlooked seagrasses that support many ocean ecologies - as detailed on the BBC1 documentary "Drowning in Plastic".

A new paper has recently argued that fishing may well be the 'best argument for seagrass conservation'. It was a striking paper for me, not because it was stating anything particularly new to me, but because it was a paper angled to articulate clearly the social and economic argument for seagrass meadow conservation – productive fisheries – and not the intrinsic ecological value of the habitat itself.

In our world today, it often feels like unless a decision can be justified economically (and specifically in the short term) then in most cases it won’t be taken. This regardless of the ecological implications that decision may have over longer time scales. Indeed, it often feels like common practice today to simply not ‘factor into the equation’ how reliant we all are on the very ecological systems that sustain us, and provide for us the basic conditions for human life on earth.

A recent Green Economy Coalition (GEC) article referenced how ‘politicians love to talk about “economic foundations”, the importance of “strong fundamentals”, and how we must avoid “structural weaknesses” that may hurt economic growth. Yet by eroding the very foundations of a coastal fishery, it’s nursery habitat, that is exactly what we are doing to our fishing industry - a tragedy of the seagrass commons. By destroying our coastal seagrass meadows - we are destroying our Natural Capital.

Let me take an example that I hope everyone can relate to.

First, let’s take the latest data for seafood landings in the UK. In 2015, UK vessels landed 708,000 tonnes of seafood with a value of £775 million. This supports a sizable seafood industry worth an estimated £6.24bn. So, seafood supports numerous jobs and communities (even if we don’t take into account the food security element). Second, let’s relate it to a species of fish that I hope everyone has heard of, ‘the fish that changed the world’, the Atlantic Cod (Gadus morhua). This fish has for a long time been the poster boy turned trouble child of the North Atlantic fishing community.

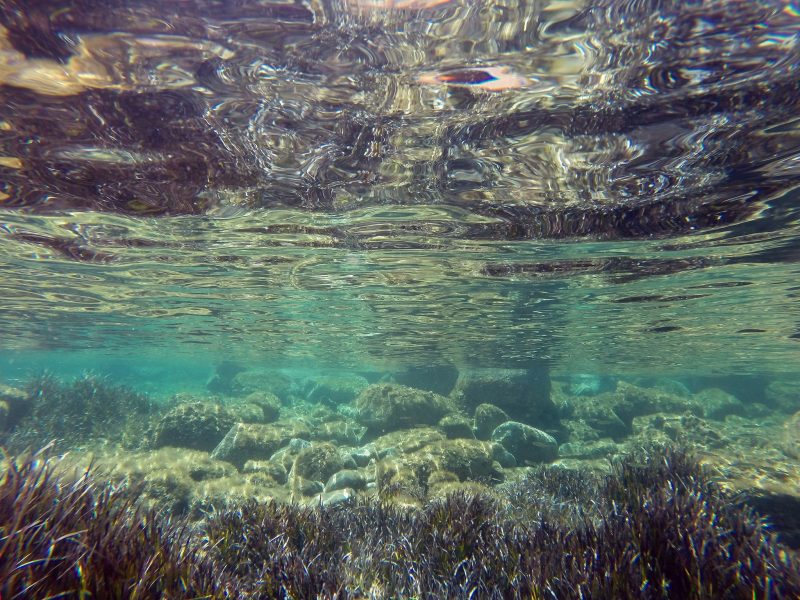

Seagrass is one of the most important coastal habitats where young ocean-going fish, such as Atlantic cod, can grow and develop before setting out on the journey of life. But these critically important habitats, are being damaged the world over, and it’s not just threatening biodiversity, but our capacity to actually have a fishery. Simply put, if there are no good habitats for baby fish to live in, that means less baby fish, and that means less adult fish in the future.

If this is not eroding the ‘fundamentals’ of the fishing industry then what is?

From my perspective, I see the growth of the Natural Capital movement as an important development because it creates a common language for articulating sustainability challenges. Although I do understand how one could be cynical about the concept.

In my world, as a marine ecologist, we often talk of ecosystem services, and how various habitats ‘provision’. In policy discussions, we talk about managing ecosystem provisioning whilst other stakeholders might talk about sustaining fish stocks. Two sides of the same coin? The current issue is that we have different communities measuring different things, which doesn’t always add up to a well-managed system. What we want is all the major stakeholders (the international community, national communities and corporations) talking the same language.

The challenge of implementing the SDGs relies on talking a common language for comparisons and metrics of performance within and between countries. The concern and pressure from governments will come from whether institutions are contributing to meeting SDGs, or making the process more difficult! So, stakeholders can be encouraged to align in the drive to meet SDGs and enable other stakeholders to transform towards sustainable trajectories.

Now the reason I am writing this blog is because a key aim of the GEC is to bring stakeholders together (from all walks of life!) to reform the global economy. In a bid for it to be greener, fairer and ultimately end poverty. Fundamentally, this involves reaching out of our professional circles to form unusual partnerships.

We should all be working towards the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) which are designed to be universal, and mean something to everybody.

“ We should all be working towards the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) which are designed to be universal, and mean something to everybody.”

We can all access different elements from markets, to marine ecosystems, and the SDGs provide us with one set of goals on which to collaborate. Yet, ultimately, we need to build a sense that we are all in this together, and that we need to work through the challenges of sustainability we face, by combining our expertise.

So, this is a call for everybody to engage in sustainability outside of their comfort zone. Only through transformative change can we build a future where everybody benefits. The SDGs are universal, EVERY country needs to achieve these goals, but to do so we need to influence the major economic actors (of which ‘big business’ is one). Natural Capital is a common framework through which we can drive conversations about the economy and sustainability.

In my opinion, the SDGs offer the definitive targets for the global community to aim for, and Natural Capital the common language to help us deliver.

I’m a founding director of an international marine conservation charity ‘Project Seagrass’. We’re an organisation which encourages people to become citizen scientists to help the cause of the SDGs. At Project Seagrass we’ve developed a web and smartphone application called ‘Seagrass Spotter’ to empower the general public to learn about (and help map!) their local seagrass meadows. We hope that people will get outside and find some in their locality. Globally at present, the fine scale mapping of coastal marine habitats is data poor and quite clearly scientists can’t be in all places at all times - this is where you all come in! If you get the time to step out of your comfort zone for the SDG’s, then please come and learn about seagrass at Project Seagrass.org.

After all, how can we hope to manage our Natural Capital if we don’t know what’s there?

- Richard Lilley, Project Seagrass