People’s voices: Participatory justice for a just transition in South Africa

A just transition cannot be achieved without paying due attention to participatory justice elements that shield vulnerable stakeholders.

Primarily anchored on a parliamentary system, South Africa’s government structure also incorporates aspects of traditional leadership and direct democracy. This is built into the country’s Constitution (1996), which not only stipulates the right to political participation (through voting) but also enshrines the concept of direct participation through various forms of engagement – a people’s government. Procedural justice, which focuses on the process and the extent to which inclusivity is a feature of it, is a core component of South Africa’s newly-defined Just Transition Framework (2022). The culture of consensus between social partners, i.e. government, organised labour, organised business and civil society, is furthermore designed to be at the core of governance. Whether people truly have a voice (directly or indirectly) on key decisions, however, remains a bone of contention in the country.

If South Africa is to secure a just transition to a green economy, the country urgently needs well-designed policy tools and participatory mechanisms that shield vulnerable stakeholders from impacts and ideally leave them better off after the transition. A just transition cannot be achieved without paying due attention to participatory justice elements as they relate to representative and direct democracy.

“ Participatory justice also involves a much greater focus on education, empowerment and capacity building of everyone – not only communities and workers but also politicians and government officials.”

South Africa has a rich history of attempts at fostering representative and direct democracy principles into policymaking. Numerous mechanisms, platforms and policies are present, on paper, to foster participatory justice in South Africa, at both national and community levels, and even within private firms. These include ward committees, aimed at bridging the gap between communities and the administrative structures of local government, as well as various ground-level citizen structures, such as municipality-wide forums, School Governing Bodies, clinic committees and Community Policing Forums.

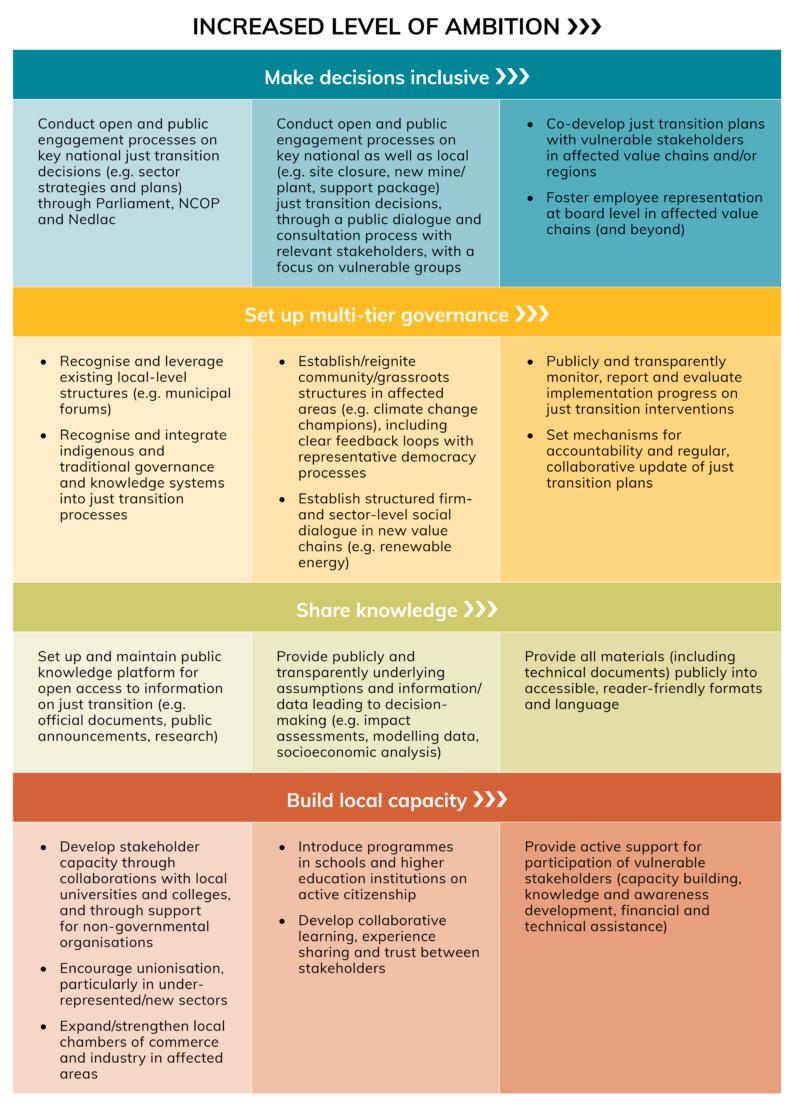

Continuum of possible interventions to enact participatory justice

Source: Montmasson-Clair, Patel & Wolpe, 2022. People's Voices: Participatory justice for a just tansition in South Africa, Pretoria: Trade & Industrial Policy Strategies.

Practically, a first step towards participatory justice would be, simply, to implement (i.e. in some cases enforce) existing mechanisms. This would require stringent monitoring, evaluation and accountability processes to avoid tick-box exercises, the bypassing of legal requirements and, at times, plain disregard to legal obligations. At the firm level, much greater emphasis on inclusive governance and ownership is needed, notably by including workers in decision-making structures. Where relevant, additional structures may also be necessary to set up adequate channels for participatory justice. In addition, effective checks and balances are also needed to avoid public decision-making being captured by special interests.

Furthermore, trust between politicians and the communities they serve must be significantly strengthened. Building trust is, however, not a quick or easy task. Openness, transparency and accountability would be a valuable first step, for example, by providing citizens with adequate opportunity to be present at key meetings, and publishing documents well in advance – a necessary but insufficient minimum standard.

Participatory justice also involves a much greater focus on education, empowerment and capacity building of everyone – not only communities and workers but also politicians and government officials. Dedicated programmes for stakeholders are necessary to build capacity. Similarly, schools could also include courses on democracy, citizenship and how to engage in decision-making processes as an active citizen. Financial obstacles, such as access to transport and communication technologies, should also be addressed.

“ Often violence and service delivery protests have become the channels through which people attempt to be heard after much disappointment and desperation.”

When we reflect on the development and success of South Africa’s 1955 Freedom Charter, combined with the democratic imperative to elevate vulnerable voices, we must recognise that representative democracy is not currently functioning well in South Africa. Yet changing this is not an impossible task. Even though most people were excluded from voting under apartheid, the underground movements found mechanisms to include the majority and marginalised voices, as the experience of the Freedom Charter demonstrates. Unfortunately, this motivation and intensity did not persist under the new democratic dispensation.

Why did non-governmental participation work during apartheid? Perhaps, it was to do with the urgency around the issues and clarity about the cause that was being fought. There was consensus that being denied basic human rights was not acceptable. People were united in their needs, in their beliefs and their rights – there was clarity and conviction. The messages were clear.

This is not the case today. In fact, people do not feel heard. Often violence and service delivery protests have become the channels through which people attempt to be heard after much disappointment and desperation. With the arrival of democracy, many activists and community leaders were absorbed into government, resulting in a gap in the leadership that had existed before. Given years of corruption and continued levels of poverty and inequality, people have progressively lost trust in government. This has also affected the way in which participation unfolds and has led to a rupture in the connect between citizens and their representatives. The clarity of the struggle, once catalysed against apartheid, can and must be rekindled around the planet, its people, and our wellbeing. In many ways, it is time to mend the broken chains of leadership and recognise the voices of all.

This blog post is based on a Trade & Industrial Policy Strategies (TIPS) paper authored by Gaylor Montmasson-Clair, Muhammed Patel and Peta Wolpe.