"I want to run away, but I don't know where to"

In winter Ulaanbaatar is one of the world's most polluted cities. We meet the Mongolian mothers battling to protect their kids from the smog

During wintertime, Mongolia’s capital Ulaanbaatar becomes one of the most polluted cities in the world, as thick smog from coal-burning power stations and stoves blankets the freezing streets. The health impacts are dire, and especially so for young children. Our partner organisation EPCRC met some Mongolian mothers to find out how they cope.

There is a famous poem which almost every Mongolian knows by heart. It goes:

Dung smoke pouring forth

I was born in a herder’s home

On the wilderness steppe

I think of my native land

But the days that Mongolians were born in a herder’s home with the smell of dung smoke have long since passed. Nowadays, most Mongolians are born with the acrid smell of coal smoke in their nostrils. When did we move from the dung smoke to the choking fumes of coal? Are we becoming forgetful from so much exposure to coal pollution? When did Ulaanbaatar, which was once known as the Asian White Angel, start hiding itself under a thick blanket of grey smoke?

Even just hearing the word “winter”, my throat starts to hurt, and I start to worry about where to buy good air pollution masks. However, as this winter set in and the streets began to fill with smog, I started to wonder – what must this seasonal torture be like for mothers with babies and young children? What kind of worries must fill their minds, when they see their city start to resemble a smoke-filled warzone?

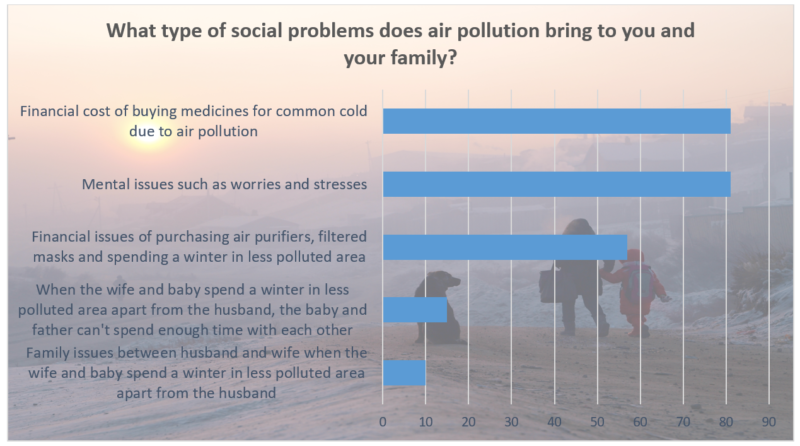

To find some answers, we ran a poll in a mother’s group on Facebook asking what type of social problems air pollution brings to you and your family.

The poll gave some surprising findings. The physical impacts of breathing such polluted air are relatively well known, but the poll showed that some of the biggest challenges that mothers face are mental health issues: worries and stresses over health and financial cost. It affects mental health both directly and indirectly: mothers who cannot leave the city feel helpless to protect their children from the pervasive smoke, and worry about the cost of medicines and preventatives. Some mothers flee the city every winter in order to save their children’s health, but face additional stress from losing their family relationships.

We wanted to better understand the mental health and financial issues caused by Ulaanbaatar’s air pollution. So we invited in two mothers for one-on-one interviews.

The first is Gerel*, 25 years old, currently living in Ulaanbaatar with her 11 month old baby and her husband. She gave birth to her baby boy last December, escaping the city’s pollution to the countryside where her parents live. The second mother is Sarnai*, 35 years old, who lives with her husband and 3 kids and manages her own business.

Finances

Gerel feels helpless in the face of Ulaanbaatar’s months of smog and smoke, and worries she cannot afford to protect her family. “There’s no way to reduce the air pollution outside, so I bought an air purifier for our house,” she said. “But good air purifiers are very expensive. It’s a big problem for a young family. My husband and I don’t depend on our parents financially, so we live off only our own salaries. But now only my husband works because I have to take care of my baby. So we had to buy a cheaper Chinese air purifier.”

“ I don’t know if it’s Mongolian tradition or not, but we have this attitude that no one should admit that they have problems. We’re just polishing ourselves on the outside.”

She admitted that the purifier was more for peace of mind than any noticeable health impact. “Personally I don’t feel the difference of having the air purifier or not, but it makes me feel happier to have it on,” she said. “I also bought an air pollution mask with filters for my son. He really doesn’t like it. He keeps trying to take it off, and he gets very upset wearing it. But that’s very expensive for us too, because you have to change the filters all the time.”

Sarnai also faced money worries brought on by Mongolia’s polluted air. “The best I can do is to keep the air in our home clean, take my kids out of the city on weekends and stay out of the city during summer holidays,” she said.

“I saw on Twitter that mothers go abroad during winter. It said that it costs 1000 USD for a month to stay in Thailand. But it’s impossible for us to go abroad during winter. My oldest child goes to school. What am I going to do about their school? I think it is hard for mothers who have many children. Somehow I have to try to survive in Mongolia.”

Family issues

Gerel chose to leave the city to give birth, hoping to protect her newborn son from early exposure to pollution – which is especially damaging for infants. She plans to go back to her parents’ place in the countryside in the winter, but worries about the impact on her marriage. “I think a family should stay together, so I don’t stay in the countryside for too long,” she said. “I only go to the countryside for the sake of my son. It’s hard to stay apart after being married with promises of living together, facing any challenges and raising our baby together. Being apart is hard for both me and my husband. It’s also hard for the kids who grow up without their dads’ care.”

Being separated from her husband isn’t just emotionally hard – it imposes more financial costs as well. “When I stay in the countryside, my husband visits sometimes – he takes a train on Friday night and arrives the next morning, stays on Saturday and heads back to the city on Sunday. But it’s tiring for my husband and costs us so much.”

For Sarnai, separating her family was too much. “I don’t think it’s a good idea to take my kids out of the city and leave my husband and my oldest child behind. If it’s really hurting my their health, I would do it to save my children’s life. But my husband should also acknowledge his responsibility as a father. I want us to raise our kids together.”

Mental health

Since giving birth, Gerel has found herself increasingly frightened by the severity of Mongolia’s pollution problem. “We just don’t know what will happen to our kids’ lungs in the future. It’s scary. I didn’t used to care so much about air pollution when I was single - I used to complain about my throat hurting, but that was it. But now I worry about how my son’s lungs are, how the pollution is affecting his body.”

Mothers in Ulaanbaatar have come together online to discuss their fears, but for Gerel it doesn’t always help. “I know that mothers share their stresses or worries on mothers’ groups on Facebook… the group that I am in now is very active. But my biggest fear is the screenshots on the posts that mothers make,” – like pictures of lungs turned black from coal dust.

“ I want to run away from Mongolia", she says. "But I don't know where to go.”

Sarnai also frequently shared her pollution worries with friends and family on Facebook. But that, she said, is relatively unusual. “Many Mongolians aren’t able to identify their own mental issues, or own up that something is making them stressed,” she said. “They hide their problems from themselves! And people don’t seek professional help when they face mental problems. I don’t know if it’s Mongolian tradition or not, but we have this attitude that no one should admit that they have problems. We’re just polishing ourselves on the outside.”

Her children’s future feels pretty bleak to Sarnai. “What’s dangerous about this air pollution is that the consequences aren’t even known at the moment,” she worries. “I think our kids will gradually become worse at studying and focusing. It’s really sad to think that the impacts of air pollution will live with our future generations for years. It's heartbreaking.”

“I want to run away from Mongolia,” she says. “But I don’t know where to.”

Who will save us?

Sometimes, it feels like our city is under the spell of a furious dragon, spewing smoke and ash. But if air pollution is the dragon, the question becomes - who will defeat this monster? Should we sit and wait for a “hero” with a big muscular body, a sharp wit, and a lightning-fast horse to save us? Or should we try to find a way by ourselves?

In the late 19thand early 20th century, London was notorious for its thick smog. Caused by the mass burning of coal for power and heat, the smog reached disastrous levels in December 1952, killing up to 12,0001 people and hospitalizing thousands more. In response to public pressure, the “Clean Air Act” was passed in 1956, forcing homes and businesses to reduce coal use and accelerating the uptake of clean fuels. By 1980, air pollution in London had fallen by 80%.

The city of London was saved by social movement, scientific pressure, effective government policies, and the cooperation of civilians and government. But who is going to save Ulaanbaatar? Air pollution is a complex problem which demands everyone’s participation. The pollution will not disappear by just clicking a button.

Should we just sit by and wait for a hero? Or should we become heroes of our own?

* Names have been changed for privacy.

Image credit: UNICEF Mongolia