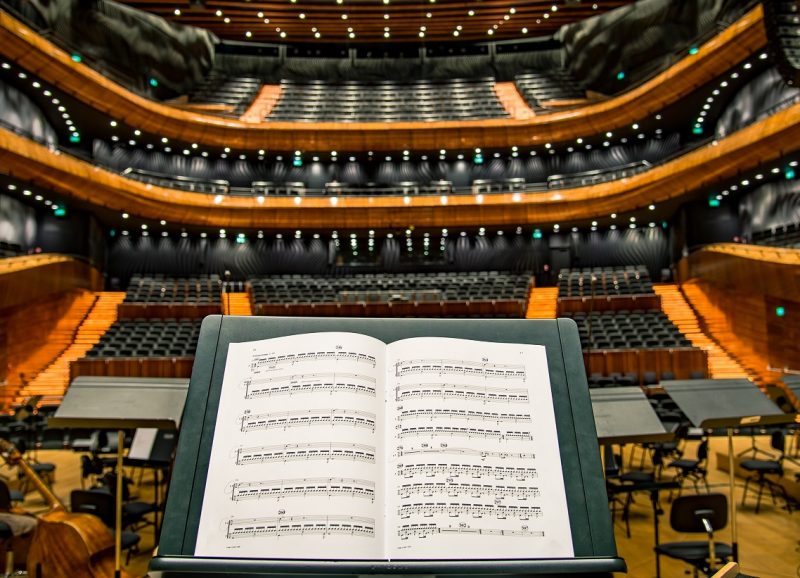

Inclusive green economy: racket or a symphony?

The tiny South Korean island of Jeju has big ambitions: by 2030 it plans to be carbon free. The province is busily expanding solar and wind technology, installing renewable storage capacity and scaling up the number of charging stations for over 300,000 electric cars over the next fifteen years.

Jeju was a fitting location for Global Green Growth Week (GGGW) last month – a gathering of practitioners, policy makers, researchers and institutions from around the world. This year GGGW focused on the inclusive dimensions of green growth. Just because the poorest depend on the environment the most there is no guarantee that green policy will improve their lives. From expensive green certification schemes to highly specialised green technologies ill-suited to local needs, ‘green’ is not by definition ‘fair’. Marianne Fay (chief economist of climate change at the World Bank) also underscored the importance of collaboration; institutions and governments working on green growth need to move from a cacophony of different approaches towards a coherent and mutually reinforcing symphony. So what is the verdict on inclusive green growth, and is it a racket or a symphony?

The size of the prize

Green growth is proving enticing to governments. From Peru to the Philippines, and from Mexico to Mongolia, governments are pursuing diverse tactics to grow their economies in a new way. Their plans are ambitious. Uganda wants to be a middle income country by 2020 and their chosen pathway is green growth; Colombia, hoping to join the OECD, is also prioritising green growth. These plans are not being relegated to the ministries of environment, but are being integrated into national development plans and handled by the ministries of finance, business and planning. Green growth is being taken seriously by people with power.

The glint of green growth is also enticing business into the ring. According to GEC member, Ethical Markets Media, the green economy has generated $7.13 trillion of cumulative private investment since 2007. We heard of how the likes of Panasonic, Toshiba and Samsung are all investing heavily in renewable energy storage as the new technological frontier. We also heard how the the natural world is inspiring a new generation of innovation: scientists at Duke University have developed more efficient wind turbine blades having studied the shape of whale fins; new solar devises have been modelled on how sunflowers track the sun. Green growth feels exciting and novel, and is pushing new frontiers of research and development.

But for the participants of GGGW the goal is still of resource efficiency not sufficiency. A group of Chinese researchers produce an annual 'Green Development Index' suggesting that their national green economy plans have proved successful by reducing energy consumption per unit of GDP (from 0.8 tons/100USD in 2005 down to under 0.3 in 2015). Yet, at the same time, overall energy consumption has continued to rise (from 150 million tons to over 300 tons in the same time period). Similarly, South Korea is pursuing an ambitious green growth strategy and recently announced its intension to shut 10 ageing coal-fired power stations by 2025 in order to pursue a greener growth model. Yet the government has not reversed its commitment to building 20 new coal-fired plants by 2022. Planetary limits appear to be a distant concept to those on the frontline of green growth.

“ Where green policy is designed in partnership with the poorest it is paving a new path out of poverty.”

Who benefits from that prize?

GGGW attracted a diverse and impressive array of researchers from around the world all closely studying the distributional aspects – real and potential – of different green growth policies. There were lots of shiny nuggets to pick through. Results from Ecuador`s Socio Bosque, an incentive based payment for ecosystem services scheme, showing that 70 per cent of the payments are transferred to small-scale landowners: evidence of how agroforestry practices on small holder farms in Nigeria are improving the yields and reducing the use of fertilisers: research into a Brazilian carbon tax, whereby if the generated income were spent on reducing sales tax, would benefit the poorest the most. Where green policy is designed in partnership with the poorest it is paving a new path out of poverty.

Yet, on more than one occasion participants referred to the choice of either scaling up green growth or making green growth inclusive. The assumption it seems is that inclusivity will slow green growth. But the experience of the Green Economy Coalition’s (GEC) network is that unlocking sustainability at scale has everything to do with inclusivity. 80% of the workforce in poor countries work, sleep and live in the informal economy; there are over 500 million small holder farms around the world supporting over 2 billion people. Designing green policy for and with the world’s poorest is all about scale.

Time and time again it is the green policies that have been designed with and for people, rather than profit alone, that have survived and have scaled up. In a developed country context, the success of Germany’s Energiewende is largely down to the fact that has helped communities take ownership of the transition (over 50% of renewable energy generation is community owned); in developing countries the pro-poor Payment for Ecosystem Service (PES) schemes in Mexico, Costa Rica and Ecuador have extended over time because they have evolved towards providing social protection for the poorest communities.

Racket or symphony?

But scale and volume does matter. The ticking clock of climate change will not wait and at present there are still too few examples of inclusive green growth happening at scale. For the GEC, the answer does not lie in policy or technology alone. Rather, it lies in inspiring people – voters, consumers, citizens – to demand change. As the GEC is learning from our dialogues in developing countries, taking green growth to scale means making it relevant to people’s lives. While the global institutions behind the green growth project are increasingly playing in harmony, and growing in volume, their rarefied symphony may not reach people on the ground. This needs to be a sound that comes from streets; only a loud drum beat of hip hop, bhangra, samba and others will take green growth to scale.

Emily Benson, Green Economy Coalition

Image credit: Radek Grzybowski / Unsplash