The green economy: a story of atonement?

Is the moral line more compelling than the bottom line? Reflecting on people power, Leviticus and economic transition.

Last week I attended a fascinating supper hosted by Tearfund – the development charity working with Christian agencies worldwide to tackle poverty – which is asking some big questions that chime with our mission at the Green Economy Coalition (GEC): what does a just and sustainable economy look like? What new models for influence will be needed to unlock change on this scale?

Tearfund gathered ten of us around a supper table to share our experiences of different campaign models. As the conversation skipped from the fate of marsupials to the tenets of Leviticus without missing a beat, I thought back to my initial interest in ‘Green Economy’ three years ago. I had tired of sitting in remote UN conference halls discussing sustainable development when the world’s elite were in Davos talking about the economy. I reached the conclusion that no amount of ‘thou shalt’ would shift the status quo. Rather, we needed to speak the language of economics – and power -- in order to kick-start a transformation. Though I am agnostic, the conversation last week challenged me to rethink.

Slippery economics

For some people at the table, who included veteran advocates, the language of economics has proved a slippery campaign tool. Just when you think you have built the vital piece of economic evidence supporting the case for change, another policy wonk presents a conflicting macro-economic dataset and the dance continues.

By contrast, the moral case offers lines which cannot be trespassed. Abolishing slavery, women’s suffrage or cancelling developing country debt were all campaigns that were fought and won on ethical lines – not by proving their economic value. The same moral imperative can and must be made for transforming our economic system so that it protects people and our planet. So, rather than building more compelling economic evidence for change, should we beating the morality drum yet harder and louder?

A story of rebirth?

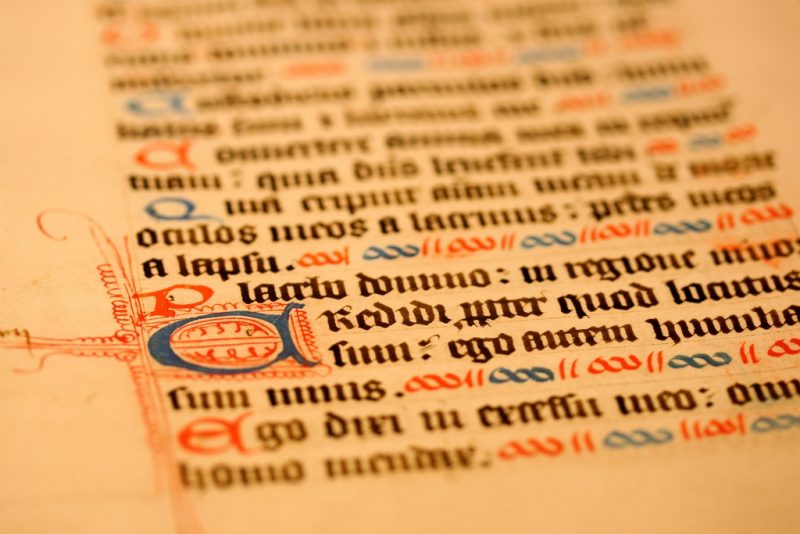

We talked about the role of story-telling for communicating the transition (see GEC’s latest thinking) and I was reminded that religious texts offer some of the most memorable stories ever told, ones that use key elements of narrative - voyage, return, tragedy, forgiveness, fear and hope. So can the scriptures help us tell this story of transition in a more compelling way?

Traditionally, the narrative for moving to green or just societies has been cast as The Quest: ‘The protagonist and some companions set out to acquire an important object or to get to a location, facing many obstacles and temptations along the way’(see Christopher Booker’s theory The Seven Basic Plots). But the scriptures also rely heavily on the theme of ‘atonement’, ‘humility’ and ‘healing’. Perhaps this story of economic transformation is more closely aligned to the final plot, Rebirth: ‘The protagonist is a villain or otherwise unlikeable character who redeems him/herself over the course of the story’. In recent decades our economies have become bloated, greedy and detached. Now the time has come to build restorative economies, ones that regenerate our natural world as well as our relationships (watch our interview with Hunter Lovins).

“ The same moral imperative can and must be made for transforming our economic system so that it protects people and our planet. So, rather than building more compelling economic evidence for change, should we beating the morality drum yet harder and louder?”

Morality and the language of faith clearly has much to offer. And yet, is it sufficient for catalysing the kind of change we need? In the context of abolishing slavery, it is no coincidence that Britain’s sugar colonies in Jamaica and Barbados had already declined following American independence, and as the industrial revolution took hold in the 18th century Britain no longer relied on slave-based goods. The moral line was enabled and accelerated by the bottom line.

Waves of moral outrage as seen during the Jubilee campaigns or the climate marches have proved instrumental for getting issues onto the global agenda. But, as the momentum of the Occupy movement wanes, it seems that mass mobilisations need also to be armed with economic arguments if they are going to move from the streets and into boardrooms and parliamentary halls.

To talk of a ‘just’ and ‘sustainable’ economy is to talk of systemic change – to our job markets, fiscal policies, financial architecture, social protection measures, institutions and much more. This is a knot of epic proportions that requires multiple brains and networks at all levels to help unravel it. This is why coalition working is so important. Within the GEC for example, we have IISD working with governments to phase out fossil fuel subsidies; IIED investigating the impact of green policies on the poorest; ILO working with governments on employment reform; Development Alternatives wiring together social enterprises in India; CANARI supporting SMEs to make a transition in the Caribbean…the list goes on.

By working independently, and then sharing the knowledge collectively, we are beginning to build up a picture of how different economic structures can function for the greater good. Together we are tackling the moral as well as the bottom line. Coalition working may not be a ‘new model of influence’ but by collaborating we are co-creating a vision of a new economy from the ashes of a broken one.

Emily Benson, Green Economy Coalition

Image credit: "Manuscript" (CC BY 2.0) by Muffet