The catch-22 of local economic development

Katie Kish explores how local communities are embracing a high-tech, home-grown "makers' movement" that offers a way out of dangerous overconsumption

The ‘small is beautiful’ vision of local, artisanal, green production for need has been a recurring feature of Romantic counterculture for two centuries. But for most of this time, community production seemed incompatible with innovation and progressive technology based on the application of science.

Over the last decade, this situation has begun to change. A network of maker spaces, hacking clubs and online peer-to-peer (P2P) design collaborations are pointing the way to a different kind of economy: high tech but local, participatory and networked. The maker movement has the potential to challenge the established business models and resilient, self-reinforcing systems of the growth economy.

There are many compelling arguments that a significant underlying cause of environmental deterioration is consumerism. The ever popular Story of Stuff dives into the specifics of this quite well. In a 2009 paper called The People Paradox, Janis Dickinson attacks this issue from a whole new perspective. She uses Earnest Becker's theory of terror management to argue that "the very things that bring us symbolic immortality often conflict with our prospects for survival". For instance, some people consume as a way to create meaning in their lives, but this path of meaning-making leads to environmental destruction. Therefore, in short, people need to be doing things that give them meaning that are beneficial to the environment.

What really sparked my interest is the booming movement of 'makers', homesteaders, and preppers. The focus of my PhD research concerns possible alternatives to consumer society that these three groups present. In focusing on these groups, I am interested in a) the extent to which open source technology (see Open Source Ecology) is transforming the possibility for local, low energy, small-scale production and maintenance of high-tech goods that have hitherto been the preserve of large scale, global industry, and b) whether participation in making/prepping/homesteading has the potential to become an effective driver of cultural-psychological and behavioural change with regard to consumerism.

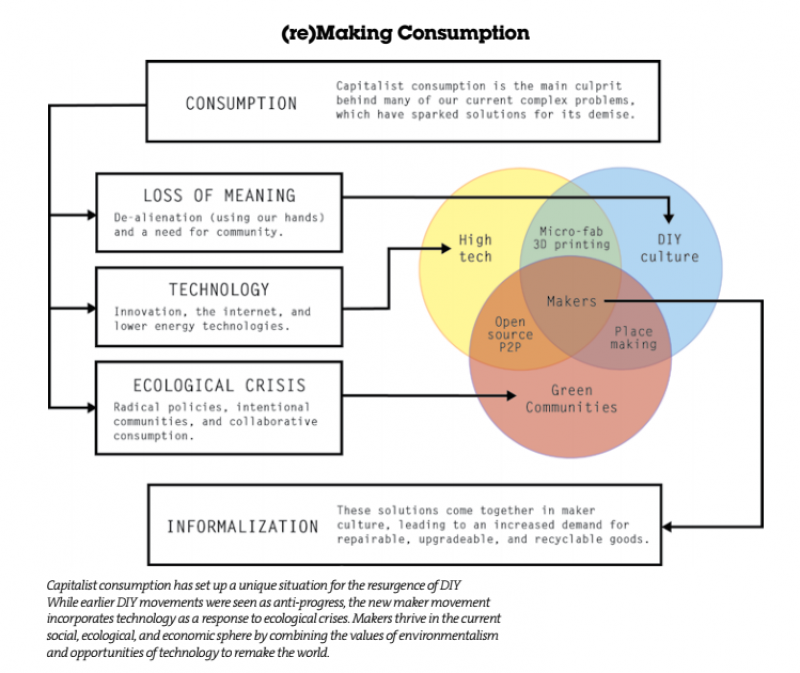

I interviewed over 160 makers, preppers and homesteaders across Canada to identify their ethical standpoints, motivations for living differently, and unique points of similarities across the groups. I cover some of the outcomes of this study in our most recent issue, Ecological Economics. The main argument is that consumption has led to a crisis of meaning, great technological innovations, and the ecological crisis - as shown in the following diagram:

My interviews with makers across Canada support this diagram. Most interestingly, all of the makers had a 'crisis of meaning' in their life - often displeasure in a stressful job - that making/DIY fixed and/or fills (either through community or reintroduction of hand/brain connections). This is largely because using our hands to create and manipulate feels good. When the children in our study were presented with materials to create, design and decorate, they fall into the maker role without hesitation.

Making reconnects the hands and brains in ways that nothing else can. In a survey with over 3, 500 knitters, the researchers found that the crafters were 'very happy' after knitting. Many had started to knit to alleviate stress, and those who took to the craft more frequently indicated higher levels of mental and emotional relief. A smaller study from 2017 found that crafting significantly reduces stress.

My study was consistent with the finding of these other studies and produced some other unsurprising results. For instance, makers have a higher propensity to repair goods instead of consume now (shocking, right?),and making seems to increase self-esteem (especially in children). There is a gender divide between various types of maker projects (women tend to knit and do pottery while men do woodworking and metal work, but not exclusively). Makers like to meet and provide community engagement, and the primary driver for becoming a 'maker' are for mental well-being and to opt out of the traditional economic system.

There are many themes among Canadian makers that I didn't predict would emerge. The two that interest me the most are a) freedom and b) anti-establishment sentiments.

Freedom & Anti-Establishment

The theme of freedom pops up a lot when you're talking to makers. For the younger generation of makers, primarily selling their goods on Etsy, making is important to them because it provides freedom to travel and to make their own schedule. For the older generation, primarily selling their goods at trade shows, making provides freedom from the slog of oppressive work environments.

For some, 'freedom' is much less benign. When making combines with homesteaders and preppers it means freedom from government intervention, protection from bureaucratic incompetence, and the ability to take care of one's self and family without relying on the government for protection, sustenance, or goods.

“ Wait for the government and it's too little, do it individually and it's too small, do it with a community and it might be enough.”

When pushed on this topic, they become passionate and defensive. There is a recognition that the future is uncertain and that we may need to rely less on global and national systems that keep us alive and safe. These makers pride themselves on having set up their own local systems to be resilient in the face of uncertainty. It is with this last group that 'anti-establishment' sentiments really start to appear.

In general, makers have an anti-establishment attitude in different ways. 60% of participants voiced dislike and distrust of multinational corporations (Walmart is specifically mentioned 90% of the time), and a significant number of participants from PEI (80%) intentionally removed themselves from mainstream culture by moving from Southern Ontario to PEI to reduce their stress or to improve their mental health – specifically depression.

With preppers and homesteaders, there is excited anticipation and a level of enthusiasm for the whole system to come crashing down. For instance, one participant said they'll be glad when it is time to "fend for myself and I'm glad that I know some great people in my hometown that will band together!" Another said that the "world will look a whole lot different and be a whole lot better when it comes to an end". Another participant said that "it is important" to him to "undermine companies and the current system". Many believed there is a major failure of democracy, a problem with greed, and a lack of trust in society that can only be fixed by becoming self-sufficient and removing one's family from that system.

So What?

What does any of this have to do with resilience in the face of environmental uncertainty? When we see groups of people 'prepping' and attempting to become free from governmental laws we're looking at threats to cohesive governance. However, these are the groups and the people that are actively and successfully building resilience and adding capacity to local communities. It's not just community gardens that these folks have – they have the tools, knowledge, and ability to sustain many people off their land with absolutely no outside help.

This got me thinking... At the same time, we are both more resilient than we have ever been and more vulnerable than ever. On the one hand we have community capacity being bolstered with preppers, homesteaders, makers, and other environmentalists and on the other hand we're faced with the greatest ecological challenges continually perpetuated by various systems of growth. My participants are both adding to resilient local population and contributing to national vulnerability because the more we turn inwards and want freedom from the state, the more we take away from state's ability to control and govern. Many of my participants would encourage movement from national to local governance, however there is a wicked dilemma there.

In his 2012 book, The Better Angels of our Nature, Stephen Pinker argues that violence in the world has declined. This is due to five forces of modernisation, one of which is the state monopoly of violence. Actions associated with strengthening local economic resilience potentially challenge all five of these forces by supporting a downscaling of economic activity and reduction of complexity. While Pinker argues that these forces are the underlying cause of a peaceful society, they also highlight the tensions within the interplay between modernisation and potential action emerging from limits discourse. A downscaling of economic or bureaucratic complexity puts into question the ability of the government to control violence and many other systems. This process results in a number of tensions for modern environmental society around topics of violence, tax bases, empathy, identity and science (I'll expand on this another time, but for the academic version you can see my paper in ecological economics).

Governmental Catch-22

How is a government or a group of people supposed to use this information? If governmental bodies attempt to regulate these groups there will be significant pushback and resistance because they are, at their core, against large scale state intervention. Or, if governments try to emulate it and force local economic development, then you'll end up with something like a room designed by a committee – lots of good ideas but nothing that makes sense as a collective.

Also, when governmental bodies get too involved they can quickly and easily strip the 'life' away from it (like too many rules at a festival). However, if the government doesn't regulate to some extent, then there may end up being ungoverned clusters that don't cohesively add up to a functioning civil society and don't obey national 'rules' and needs.

Various groups across Canada are realizing things are 'bad', in different ways. Some are focused on energy, others on water, and some on food. The best thing for the government to do, is to take those people seriously and empower them. Take some of the 'empowerment' (money) away from organizations and companies that I haven't even mentioned here – the multi-nationals that aren't contributing to resilience in any way, shape or form – and redistribute some of that 'empowerment' (money & capacity) back to communities.

There are ways for the government to show that they support the environmental and resilient movements being produced all over the country, and if they would buy into those movements, then there might be less of an anti-establishment sentiment within some of the groups.

If national and local governments can empower these communities of resilience to emerge organically and help them to connect together, then there may be a chance to weave a Canadian web of resilience against shortages of food, climate change, water scarcity, etc.

I'll leave you for today with a quote from Richard Heinburg:

"...wait for the government and it's too little, do it individually and it's too small, do it with a community and it might be enough".

Katie Kish, Alternatives Journal

This article is re-posted with permission from Canada's Alternatives Journal, where it originally appeared.

Image credit: "Build your own 3D printer workshop" (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) by gillespinault

Some Further Reading:

Anderson, Chris. 2012. Makers: The New Industrial Revolution. First edition. New York: Crown Business.

Arndt, Jamie, Sheldon Solomon, Tim Kasser, and Kennon M. Sheldon. 2004. “The Urge to Splurge: A Terror Management Account of Materialism and Consumer Behavior.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 14 (3): 198–212. doi:10.1207/s15327663jcp1403_2.

Becker, Ernest. 1973. The Denial of Death. New York: Free Press Paperbacks.

Dickinson, Janis. 2009. “The People Paradox: Self-Esteem Striving, Immortality Ideologies, and Human Response to Climate Change.” Ecology and Society 14 (1): 34.

Greenberg, Jeff, Tom Pyszczynski, and Sheldon Solomon. 1986. “The Causes and Consequences of a Need for Self-Esteem: A Terror Management Theory.” In Public Self and Private Self, edited by Roy F. Baumeister, 189–212. Springer Series in Social Psychology. Springer New York. http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4613-9564-5_10.

Hatch, Mark. 2013. The Maker Movement Manifesto: Rules for Innovation in the New World of Crafters, Hackers, and Tinkerers. 1 edition. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Jackson, Tim. 2009. Prosperity without Growth: Economics for a Finite Planet. London; New York: Earthscan.

Kasser, Tim. 2003. The High Price of Materialism. 1 edition. Cambridge, Mass.: A Bradford Book.

Kasser, Tim, and Kennon M. Sheldon. 2000. “Of Wealth and Death: Materialism, Mortality Salience, and Consumption Behavior.” Psychological Science 11 (4): 348–51. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00269.

Victor, Peter A. 2008. Managing without Growth Slower by Design, Not Disaster. Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.