Dasgupta's economics can't fix the extinction crisis

The latest review into environmental economics replicates the flaws of its predecessors - and will be equally ineffective as a result

The GEC Insights series explores the intersection of environment and economics, written by leading thinkers from the worlds of business, government and civil society. Part of our Economics for Nature project, they bring together diverse perspectives to answer the question: how can we re-design our economies to protect and restore nature?

In this article, Victor Anderson, Visiting Professor at the Global Sustainability Institute, Anglia Ruskin University, casts a critical eye over the Dasgupta review on natural capital, and asks why we should expect this review to succeed where others have failed.

One of the ways the UK Government has aimed to contribute to global debate about the ecological crisis is through commissioning a review of the Economics of Biodiversity. This is being led by the distinguished Cambridge-based development economist, Sir Partha Dasgupta, assisted by a group of civil servants, academics and analysts based in the Treasury.

The economics of biodiversity is potentially one of the most important topics imaginable: the relationship between how the natural world organizes itself and how humans organize our social world, which is principally through economics and business.

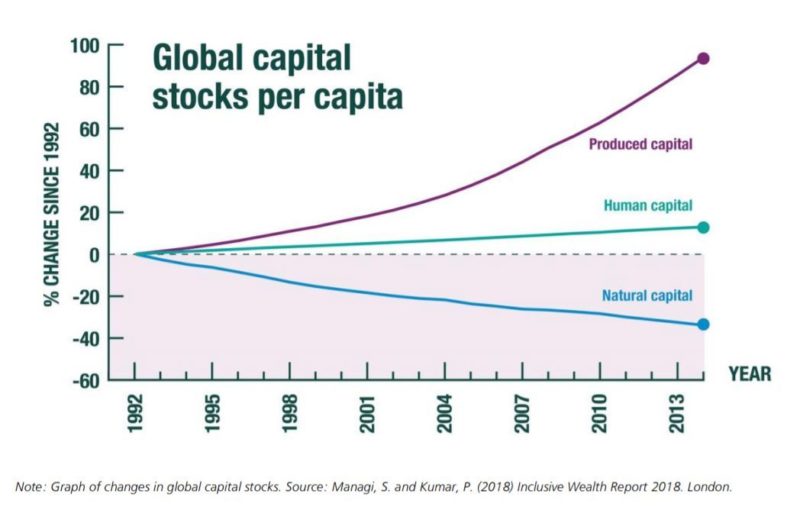

The Dasgupta Review has now brought out its Interim Report. It provides a striking overview of the different ways in which the natural world is falling apart around us (what they call negative “global trends in the capacity of nature to sustain contributions to good quality of life”). The economics and the science come together in a dramatic graph on page 26 which shows “produced capital” (machinery and buildings) keeping on increasing, whilst in almost a mirror-image “natural capital” is in steady decline.

The starkness of the overall message is clear. But the interim report itself has some serious shortcomings.

Compromise and confusion

Biodiversity and the health of the biosphere are very difficult to measure, and total “natural capital” has proved in practice to be impossible to quantify with any degree of reliability. There is no equivalent metric for biodiversity that can compare to increases in global average temperatures in climate change – easily measured, understood and communicable.

This is a genuine problem, but the Report’s attempted solution appears quite desperate. It chooses as its main global measures Net Primary Production (NPP), which is basically a measurement of how much living material is created through photosynthesis, and total biomass, which is a measurement of how much living material exists at a particular time (para 1.23). Neither of these actually measure biodiversity, environmental quality, or the health or resilience of ecosystems.

What seems to underlie this is the treatment of “provisioning services” as the paradigm case of the benefits nature provides to humans. These services largely are about quantity – e.g. of timber or wheat – and not so much about diversity. However “regulating services” – such as the regulation of air and water quality, and pest regulation – depend much more on diversity and it is surely not appropriate to measure them in the same way.

My main problem with the report, however, is that it does not engage with what happened to similar sets of ideas put forward by its predecessors - above all, the Pearce Report 30 years ago and the TEEB reports around 10 years ago.

“ Since tax and subsidy reform has been a central demand of environmental economics for almost 40 years, at this point we can legitimately ask - why have governments not done it already?”

The report asks, apparently naively: “Why are our individual actions working against our collective interest …?” This frames the issue as being about the actions of individuals, when in fact we all live in the context of social organisations, above all governments, companies, and markets. The world economy is dominated by large corporations and flows of finance, having as their prime objective the maximization of profit. This is achieved largely by minimising costs, and where possible passing those costs on to others. Firms don’t pay for the impact of their carbon emissions, for example, unless governments deliberately introduce some mechanism to make them do so.

Not seeing the woods for the biomass

The report doesn’t talk about profit maximization, but it does acknowledge that “the current structure of market prices works against our biosphere.” This implies a need for measures of government intervention to put things right, through taxes and getting rid of damaging subsidies.

However, since tax and subsidy reform has been a central demand of environmental economics for almost 40 years, at this point we can legitimately ask why governments haven’t already done it. Here we see the danger of separating economics off from the study of politics. Those same corporations that are busy maximizing their profits are also often at work minimizing any forms of government intervention that may get in the way.

Market-based environmental economics theory is in that sense incomplete, because it doesn’t examine the institutional and political factors – and even some straightforwardly economic ones - which prevent its recommendations from being fully implemented. For example, the EU Emissions Trading System was in theory a good idea, but its effectiveness was undermined by consistent lobbying to exclude various industries and push down the price of emissions permits.

Another mainstay of environmental reports like this also appears in Dasgupta: instead of GDP as a measure of success, let’s have NDP, a net figure which takes off depreciation, including the “depreciation” of “natural capital” and “human capital”.

This has been suggested many times and in various versions over the decades, but outside of Bhutan and New Zealand, again governments simply haven’t done it. Again, we must ask the awkward question of why not? It turns out that the profit share of the economy is very sensitive to changes in the rate of growth of GDP. It follows from this that aiming to maximise GDP growth is a very convenient proxy for maximizing profit at the level of the national economy.

Flawed in the fundamentals?

It is hard to see how this report could have turned out very differently, given its remit. The Dasgupta Review – so far, and this is only its interim report – demonstrates the limitations of mainstream environmental economics, even when sincere efforts are being made to make it useful.

What is missing from this interim report is not only the discussion of difficult “options for change” which are promised for the final report – presumably policy recommendations for food, energy and transport for example – but also some key institutional and political questions.

Chief amongst these must be the urgent need to reform financial markets which constantly pressure corporations to maximise short-term financial gains, and reforming the nature, objectives and governance of the corporations themselves. Then we would come somewhere near to having a package of policies which can actually achieve the task the Dasgupta Review sets out to accomplish.

- Victor Anderson, Visiting Professor, Global Sustainability Institute