Conservation and discrimination: case studies from Nepal’s national parks

How can we stop badly designed conservation policies from entrenching historical injustice among Indigenous and marginalised communities?

This article appears as part of our blog series, co-developed together with IIED's Natural Resources group, Putting social and environmental justice at the core of conservation, climate and development, in which we scrutinise differing approaches to tackling the nature and climate crises through the lens of equality and intersectional justice.

Land and natural resources are fundamental to the culture, social relations, and identity of Nepal’s Indigenous communities. Yet conservation policies and programmes, natural resource extraction and mega-development projects have deprived many communities of resources such as land, forest and water.

This abuse and discrimination dates back centuries to when powerful families heavily taxed land ownership in the form of tribute for agricultural products, and unpaid and forced labour. To escape this abusive taxation, many Indigenous communities chose not to claim land ownership.

Nepal’s government only began conducting land surveys and issuing legally-recognised land ownership certificates some five to six decades ago. Many Indigenous communities failed to obtain the legal documents to back their land claims, leaving many landless and subject to evictions and continued economic exploitation.

“ Having suffered a long history of exploitation and injustice, Indigenous communities are challenging discrimination by organising, mobilising and employing legal tactics to seek remedy for harms.”

The government policies governing land tenure were formulated without Indigenous consultation and are designed to promote taxation and government control of conservation areas rather than recognise the legitimate land claims of Indigenous communities. Many Indigenous families and communities remain landless, poor and marginalised from the tilling land.

Having suffered a long history of exploitation and injustice, Indigenous communities are challenging discrimination by organising, mobilising and employing legal tactics to seek remedy for harms based on national and international legal instruments.

CSRC’s action research with Indigenous communities

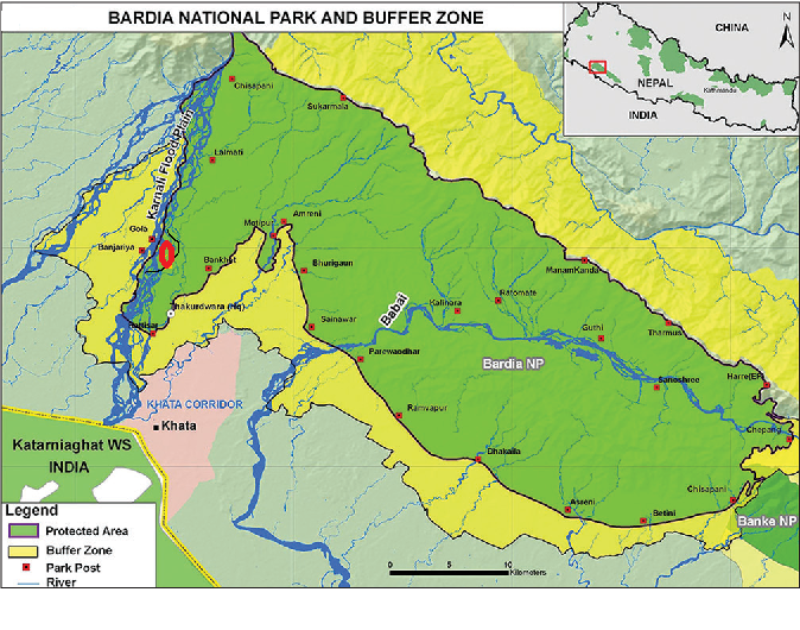

Community Self Resilience Center (CSRC) and Amnesty International co-designed an action research project with the Indigenous groups of Chitwan and Bardiya National in central and western Nepal. Here, we focus on the research highlighting the abuse of Tharu Peoples and communities in Geruwa, neighbouring the Bardiya National Park.

CSRC organised a five-day training workshop on community-based participatory action research in Thakurdwara, Bardiya district. Fifteen local community representatives were selected and mobilised to implement the research.

CSRC and Amnesty International facilitated the training while the representatives analysed historical marginalisation of the Tharu. All 15 researchers were Tharu speaking; 10 belonged to the Tharu community and five were from the same area. Eleven were female and four were male.

Forced evictions: the case of Bardiya

As national parks, hunting reserves and protected areas are created, people living in those areas are regularly evicted. The police and army destroy houses, set fire to villages and their elephants ruin crops. Decades of revisions to Nepal’s constitution, laws, policies and system of governance do not show any signs of stopping these ongoing abuses.

International organisations including the World Wildlife Fund for Nature (WWF) have ignored the issues of marginalised communities and Indigenous peoples’ rights. Nepal has already established 20 protected areas, including 12 national parks, one wildlife reserve, one hunting reserve, six conservation areas and 13 buffer zones. These occupy 23.39% of the land.

The Bardiya National Park, established in 1976, is the largest and covers 968 km². A further 327 km² surrounding the park was designated a ‘buffer zone’ – on a national park or reserve periphery, created to “provide facilities to use forest resources on a regular and beneficial basis for the local people” (PDF).

“ Our participatory research found that since the mid-1980s, the Bardiya National Park authorities have evicted around 300 Geruwa households, and 274 from the Tharu community. Many families had no choice but to resettle on government lands from which they were evicted again and again.”

Tharu communities originally lived in Dang district but migrated to other districts including Bardiya because of injustices committed by large landholders in the Rana era. The Tharu settled in Bardiya and cleared unused lands for agricultural purposes. This new-found economic independence improved livelihoods until they, and other locals, were evicted from their land to make way for the national park.

Since 1976, restrictions have prevented the Tharu communities from entering the jungle to carry out daily livelihoods activities such as cattle herding, gathering forest products, fishing and collecting herbs and food. Being dispossessed of their lands and resources, and with their economic activities restricted, the Tharu have lost their collective traditional knowledge developed over centuries.

Without using any formal legal process, the national park restricts use of any land within the park boundary. The Tharu are not allowed to settle, access natural resources, or “occupy, clear, reclaim or cultivate any part or grow or harvest any crop" (PDF).

Action against eviction

The right to free, prior and informed consent before taking actions on lands of Indigenous peoples guaranteed under the International Labour Organisation (ILO) convention No 169 (ratified by Nepal in 2007) and the United Nations Declaration on Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) increased awareness of the land rights of Indigenous communities and has spurred action.

Sixty-seven families from the Geruwa community collectively filed a supreme court case in 2006 asking for the return of their land.

The court acknowledged the harms the families had suffered but quashed their writ petition. On 2 April 2012, the court concluded there was no need to order public agencies (National Park Office, Buffer Zone Management Committee and the National Park and Wildlife Conservation Department) to take remedial actions because these agencies had written to the court saying they would provide compensation if all required documents (for example land ownership certificates and tax receipts) substantiated the applicants’ claims for compensation.

Eight and a half years later, in November 2020, communities had still not received compensation. The chief warden of the Bardiya National Park confirmed there were still no plans to provide compensation or assist resettlement of these families.

When asked about how the authorities were addressing peasants' grievances, the chief warden of the Bardiya National Park Office stated: “the boundary of the national park is the western side of Geruwa river and now the Geruwa river came to the village side. It is therefore difficult to give them access to their land that came inside the boundary.”

For Tharu communities, the sense of social and communal belongingness stems from the lands and territory they inhabit; being evicted from these lands is painful. The same is true of people who have been cultivating land for a long time, have been unable to register in their own name, and been repeatedly evicted by the park administration.

Championing Indigenous rights

Despite decades of legal reforms in Nepal, the issues remain same; the evicted families are cultivating others' land as sharecroppers. Legitimate landowners are landless due to the forced eviction from the national park.

The government and legal system’s failures to protect Indigenous rights illustrates why it is more important than ever that conservation actors act in concertation and allyship with Indigenous groups. Yet the fortress conservation model persists in Nepal and numerous countries throughout the world.

Nepal’s Indigenous peoples have the right to access natural resources and lands. In the case of Bardiya National Park, the Tharu and other local peoples are prevented from enjoying their rights to their land, to food and food sovereignty, to housing, to property and ultimately the right to live with dignity.

Activists will continue to champion Tharu demands for the government of Nepal to provide compensation and lands for Tharu people without any delay.

- Jagat Deuja, Executive Director of Community Self Reliance Centre, Nepal.