Climate finance isn't enough. We need debt cancellation

As G7 finance ministers meet in Japan, our friends at Debt Justice outline why the global north must end climate usury

As G7 Finance Ministers meet in Japan this week, a debt crisis is ravaging across the global south. The latest research finds that 54 countries are currently spending so much on debt repayments that they’re not able to adequately meet the economic and social needs of citizens. And the situation could get much worse, as interest rates rise, markets destabilize and the war in Ukraine pushes up food and energy prices.

Climate change and debt: a devastating combination

But what has this got to do with the climate crisis? The answer is simple: every dollar that a government in the global south spends on repaying debt to its northern creditors, is a dollar that could have been spent on alleviating and preparing for the climate crisis.

In many cases, debt repayments far outweigh the resources available for climate action. Figures published by Debt Justice show that 34 lower income countries are spending five times more on debt repayments than they are on addressing the impacts of the climate crisis.

In 2022, Pakistan was hit by devastating floods brought on by the climate crisis. The impact was enormous. 33 million people were affected and over $40 billion worth of damage was caused. The people of Pakistan have done very little to create the climate crisis, yet this huge bill has landed at their feet, not to mention the non-economic damages experiences such as disrupted healthcare and psychological trauma. Meanwhile, Pakistan is due to pay over $20 billion in debt repayments to external creditors this year alone,1 money that would be far better used to recover and rebuild after the floods.

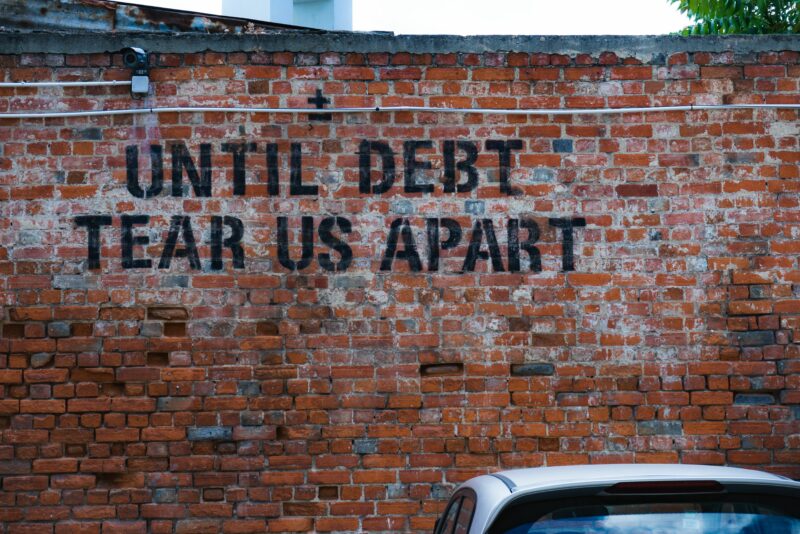

“ We cannot achieve climate justice without debt justice, and we cannot achieve debt justice without debt cancellation. We must keep pushing now, especially in the face of false solutions and smokescreens.”

While some international actors have offered to provide some funds to support Pakistan, nearly all of this will be provided as loans, adding to debt levels. In fact, most official climate finance is provided as loans – 71% according to OECD figures. This means even funds designed to alleviate the worst climate impacts are themselves adding to debt burdens, and unfairly forcing the cost of the climate crisis onto lower income countries.

But there’s more. To repay debt, countries need to be able to generate foreign exchange. To do this, many are turning to their natural resources as a source of income, including fossil fuels, with key institutions like the IMF and World Bank actively encouraging these activities. For example, the IMF and Argentinian government are pushing the development of fracking in the Vaca Muerta oil and gas field in Patagonia to solve the country’s debt crisis and wider economic problems, despite resistance from many Argentinian groups.

The debt crisis is exacerbating the climate crisis. What now?

One of the most positive developments at last year’s COP27 climate talks was the emergence of the Bridgetown Initiative under the leadership of Prime Minister Mia Mottley, which aims to put unsustainable debt at the heart of global conversations about climate justice. With French President Macron signed up and the Paris Summit set for June, this increased focus on debt relief is encouraging.

But it needs to go much further. The proposals considered so far fail to adequately address the debt crisis, proposing small-scale solutions like Climate Resilient Debt Clauses and debt swaps that miss the mark. What’s worse, these proposals would exacerbate the debt crisis by encouraging even more lending to global south countries. No matter how innovative or shiny the packaging, providing new loans is not the answer.

This isn't going to cut it. What we urgently need is debt cancellation, across all creditors and for all countries that need it, and climate finance given as grants, not as loans.

Roadblocks to action

What’s blocking progress towards debt relief negotiation? Again, the answer is simple: private creditors aren’t playing ball.

Private creditors are collectively owed about one third of all lower income country external debt, and because of the high interest rates they charge on their loans, are set to make billions in profit if they’re repaid in full.

Creditor governments in the global north agree that private creditors should participate in debt relief, but assume they will do so voluntarily. This hasn't happened, and why would it when big profits are at stake?

Zambia for example was forced to default on one of its bonds in 2020 after private creditors refused the request for a debt suspension when the pandemic hit. A few months later, Zambia applied for debt relief, but private creditors continue to block progress. BlackRock – Zambia's largest bondholder – could make up to 110% in profit if repaid in full. Zambia has been waiting over two years for debt relief, meanwhile the country continues to experience the impacts of the climate crisis, including catastrophic flooding earlier this year.

To get things moving, private creditors need to be forced to the table. Almost all international debt contracts are enforced through UK or New York Courts, so the UK and US have a special responsibility to act. We cannot achieve climate justice without debt justice, and we cannot achieve debt justice without debt cancellation. We must keep pushing now, especially in the face of false solutions and smokescreens.

If you’re in the UK, you can sign our latest petition calling on the UK government to hold private creditors accountable.

For more information on the links between the debt and climate crises read our report with Climate Action Network International, ‘The debt and climate crises: Why climate justice must include debt justice’.

- Tess Woolfenden, Debt Justice